Stamping, shouting, and making a loud noise with rattles, drums and tambourines were all thought to drive hostile forces away from vulnerable women, such as those who were pregnant or about to give birth, and from children - also a group at risk, liable to die from childhood diseases. Headrest of a scribe protected with protective deities including the god Bes, who warded off evil demons from the headrest's owner as he slept. None of these uses of magic was disapproved of - either by the state or the priesthood. Knowing the names of these beings gave the magician power to act against them. All deities and people were thought to possess this force in some degree, but there were rules about why and how it could be used. Headrest of a scribe protected with protective deities including the god Bes, who warded off evil demons from the headrest's owner as he slept Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.

Only foreigners were regularly accused of using evil magic. This gave them akhw power, a superior kind of magic, which could be used on behalf of their living relatives. The wands were symbols of the authority of the magician to summon powerful beings, and to make them obey him or her.

Many spells included speeches, which the doctor or the patient recited in order to identify themselves with characters in Egyptian myth. This page has been archived and is no longer updated.

Many spells included speeches, which the doctor or the patient recited in order to identify themselves with characters in Egyptian myth. This page has been archived and is no longer updated.

Other amulets were designed to magically endow the wearer with desirable qualities, such as long life, prosperity and good health. Statue of Sekhmet The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. Museums with good collections of Egyptian magical objects include the British Museum and the Petrie Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Museo Egizio in Turin, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Though magic was mainly used to protect or heal, the Egyptian state also practised destructive magic. To be effective all the words, especially the secret names of deities, had to be pronounced correctly. The patient then licked these off, to absorb their healing power. The words might be spoken to activate the power of an amulet, a figurine, or a potion. Dr Geraldine Pinch has taught Egyptology at Cambridge University and is now a member of the Oriental Institute, Oxford University. The magic water was then drunk by the patient, or used to wash their wound. Magic was not so much an alternative to medical treatment as a complementary therapy. The names of foreign enemies and Egyptian traitors were inscribed on clay pots, tablets, or figurines of bound prisoners.

The story ends with the promise that anyone who is suffering will be healed, as Horus was healed. Surviving medical-magical papyri contain spells for the use of doctors, Sekhmet priests and scorpion-charmers. Metal wands representing the snake goddess Great of Magic were carried by some practitioners of magic. These conspirators got hold of a book of destructive magic from the royal library, and used it to make potions, written spells and wax figurines with which to harm the king and his bodyguards. These potions might contain bizarre ingredients such as the blood of a black dog, or the milk of a woman who had born a male child. Real lector priests performed magical rituals to protect their king, and to help the dead to rebirth. Amulets were another source of magic power, obtainable from 'protection-makers', who could be male or female. A statue of King Ramesses III (c.1184-1153 BC), set up in the desert, provided spells to banish snakes and cure snakebites. Last updated 2011-02-17. The fiercest gods and goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon were summoned to fight with, and destroy, every part of Apophis, including his soul (ba) and his heka. Magic provided a defence system against these ills for individuals throughout their lives. Semi-circular ivory wands - decorated with fearsome deities - were used in the second millennium BC. Through heka, symbolic actions could have practical effects. Protective or healing spells written on papyrus were sometimes folded up and worn on the body. By the first millennium BC, their role seems to have been taken over by magicians (hekau). Anything that remained was dissolved in buckets of urine. Read more. Lower in status were the scorpion-charmers, who used magic to rid an area of poisonous reptiles and insects. Supernatural 'fighters, such as the lion-dwarf Bes and the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, were represented on furniture and household items. Some of the ivory wands may have been used to draw a protective circle around the area where a woman was to give birth, or to nurse her child. Their job was to protect the home, especially at night when the forces of chaos were felt to be at their most powerful. These objects were then burned, broken, or buried in cemeteries in the belief that this would weaken or destroy the enemy. Midwives and nurses also included magic among their skills, and wise women might be consulted about which ghost or deity was causing a person trouble. From everyday healing to treachery in the court of King Ramesses III, magic pervaded every aspect of ancient Egyptian life. Acting out the myth would ensure that the patient would be cured, like Horus. Bes and Taweret also feature in amuletic jewellery. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more. BBC 2014 The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Healing magic was a speciality of the priests who served Sekhmet, the fearsome goddess of plague. The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. By Dr Geraldine Pinch Only a small percentage of Egyptians were fully literate, so written magic was the most prestigious kind of all. The conspirators were tried for sorcery and condemned to death. The power in these words and images could be accessed by pouring water over the cippus. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. The treacherous harem ladies would have been able to obtain such substances but the plot seems to have failed.

The most respected users of magic were the lector priests, who could read the ancient books of magic kept in temple and palace libraries. Once a dead person was declared innocent they became an akh, a 'transfigured' spirit. Magical figurines were thought to be more effective if they incorporated something from the intended victim, such as hair, nail-clippings or bodily fluids. The wands were engraved with the dangerous beings invoked by the magician to fight on behalf of the mother and child. Her books include Votive Offerings to Hathor (Griffith Institute) and Handbook of Egyptian Mythology (ABC-Clio). Private collections of spells were treasured possessions, handed down within families. It is not until the Roman period that there is much evidence of individual magicians practising harmful magic for financial reward. There were even spells to help the deceased when their past life was being assessed by the Forty-Two Judges of the Underworld. Music and dance, and gestures such as pointing and stamping, could also form part of a spell. Since demons were thought to be attracted by foul things, attempts were sometimes made to lure them out of the patient's body with dung; at other times a sweet substance such as honey was used, to repel them. Collections of healing and protective spells were sometimes inscribed on statues and stone slabs (stelae) for public use. The dead person's soul, usually shown as a bird with a human head and arms, made a dangerous journey through the underworld. This might involve abstaining from sex before the rite, and avoiding contact with people who were deemed to be polluted, such as embalmers or menstruating women. In popular stories such men were credited with the power to bring wax animals to life, or roll back the waters of a lake. Human enemies of the kings of Egypt could also be cursed during this ceremony. A spell usually consisted of two parts: the words to be spoken and a description of the actions to be taken. Amulets of Ancient Egypt by Carol Andrews (British Museum Press, 1994), 'Witchcraft, Magic and Divination in Ancient Egypt' by JF Borghouts in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East edited by JM Sasson (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1995), Magic in Ancient Egypt by Geraldine Pinch (British Museum Press/University of Texas Press, 1994). Private collections of spells were treasured possessions, handed down within families. Magical figurines were thought to be more effective if they incorporated something from the intended victim, such as hair, nail-clippings or bodily fluids. The mummified body itself was protected by amulets, hidden beneath its wrappings. In major temples, priests and priestesses performed a ceremony to curse enemies of the divine order, such as the chaos serpent Apophis - who was eternally at war with the creator sun god. Some have inscriptions describing how Horus was poisoned by his enemies, and how Isis, his mother, pleaded for her son's life, until the sun god Ra sent Thoth to cure him. A type of magical stela known as a cippus always shows the infant god Horus overcoming dangerous animals and reptiles. They are shown stabbing, strangling or biting evil forces, which are represented by snakes and foreigners. Egyptians of all classes wore protective amulets, which could take the form of powerful deities or animals, or use royal names and symbols. In Egyptian myth, magic (heka) was one of the forces used by the creator to make the world. Angry deities, jealous ghosts, and foreign demons and sorcerers were thought to cause misfortunes such as illness, accidents, poverty and infertility. This kind of magic was turned against King Ramesses III by a group of priests, courtiers and harem ladies. The most respected users of magic were the lector priests Priests were the main practitioners of magic in pharaonic Egypt, where they were seen as guardians of a secret knowledge given by the gods to humanity to 'ward off the blows of fate'. Collections of funerary spells - such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead - were included in elite burials, to provide esoteric magical knowledge. The spells were often targeted at the supernatural beings that were believed to be the ultimate cause of diseases. Detail from an ivory wand

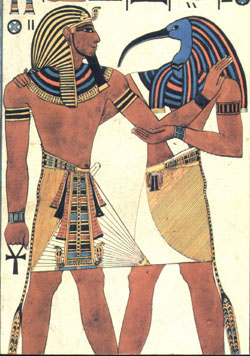

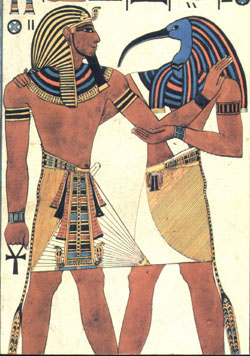

Ideally, the magician would bathe and then dress in new or clean clothes before beginning a spell. The doctor may have proclaimed that he was Thoth, the god of magical knowledge who healed the wounded eye of the god Horus. Images of Apophis were drawn on papyrus or modelled in wax, and these images were spat on, trampled, stabbed and burned. This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. Dawn was the most propitious time to perform magic, and the magician had to be in a state of ritual purity. Horus Another technique was for the doctor to draw images of deities on the patient's skin. All Egyptians expected to need heka to preserve their bodies and souls in the afterlife, and curses threatening to send dangerous animals to hunt down tomb-robbers were sometimes inscribed on tomb walls.

Only foreigners were regularly accused of using evil magic. This gave them akhw power, a superior kind of magic, which could be used on behalf of their living relatives. The wands were symbols of the authority of the magician to summon powerful beings, and to make them obey him or her.

Many spells included speeches, which the doctor or the patient recited in order to identify themselves with characters in Egyptian myth. This page has been archived and is no longer updated.

Many spells included speeches, which the doctor or the patient recited in order to identify themselves with characters in Egyptian myth. This page has been archived and is no longer updated. Other amulets were designed to magically endow the wearer with desirable qualities, such as long life, prosperity and good health. Statue of Sekhmet The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. Museums with good collections of Egyptian magical objects include the British Museum and the Petrie Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Museo Egizio in Turin, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Though magic was mainly used to protect or heal, the Egyptian state also practised destructive magic. To be effective all the words, especially the secret names of deities, had to be pronounced correctly. The patient then licked these off, to absorb their healing power. The words might be spoken to activate the power of an amulet, a figurine, or a potion. Dr Geraldine Pinch has taught Egyptology at Cambridge University and is now a member of the Oriental Institute, Oxford University. The magic water was then drunk by the patient, or used to wash their wound. Magic was not so much an alternative to medical treatment as a complementary therapy. The names of foreign enemies and Egyptian traitors were inscribed on clay pots, tablets, or figurines of bound prisoners.

The story ends with the promise that anyone who is suffering will be healed, as Horus was healed. Surviving medical-magical papyri contain spells for the use of doctors, Sekhmet priests and scorpion-charmers. Metal wands representing the snake goddess Great of Magic were carried by some practitioners of magic. These conspirators got hold of a book of destructive magic from the royal library, and used it to make potions, written spells and wax figurines with which to harm the king and his bodyguards. These potions might contain bizarre ingredients such as the blood of a black dog, or the milk of a woman who had born a male child. Real lector priests performed magical rituals to protect their king, and to help the dead to rebirth. Amulets were another source of magic power, obtainable from 'protection-makers', who could be male or female. A statue of King Ramesses III (c.1184-1153 BC), set up in the desert, provided spells to banish snakes and cure snakebites. Last updated 2011-02-17. The fiercest gods and goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon were summoned to fight with, and destroy, every part of Apophis, including his soul (ba) and his heka. Magic provided a defence system against these ills for individuals throughout their lives. Semi-circular ivory wands - decorated with fearsome deities - were used in the second millennium BC. Through heka, symbolic actions could have practical effects. Protective or healing spells written on papyrus were sometimes folded up and worn on the body. By the first millennium BC, their role seems to have been taken over by magicians (hekau). Anything that remained was dissolved in buckets of urine. Read more. Lower in status were the scorpion-charmers, who used magic to rid an area of poisonous reptiles and insects. Supernatural 'fighters, such as the lion-dwarf Bes and the hippopotamus goddess Taweret, were represented on furniture and household items. Some of the ivory wands may have been used to draw a protective circle around the area where a woman was to give birth, or to nurse her child. Their job was to protect the home, especially at night when the forces of chaos were felt to be at their most powerful. These objects were then burned, broken, or buried in cemeteries in the belief that this would weaken or destroy the enemy. Midwives and nurses also included magic among their skills, and wise women might be consulted about which ghost or deity was causing a person trouble. From everyday healing to treachery in the court of King Ramesses III, magic pervaded every aspect of ancient Egyptian life. Acting out the myth would ensure that the patient would be cured, like Horus. Bes and Taweret also feature in amuletic jewellery. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more. BBC 2014 The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Healing magic was a speciality of the priests who served Sekhmet, the fearsome goddess of plague. The soul had to overcome the demons it would encounter by using magic words and gestures. By Dr Geraldine Pinch Only a small percentage of Egyptians were fully literate, so written magic was the most prestigious kind of all. The conspirators were tried for sorcery and condemned to death. The power in these words and images could be accessed by pouring water over the cippus. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. The treacherous harem ladies would have been able to obtain such substances but the plot seems to have failed.

The most respected users of magic were the lector priests, who could read the ancient books of magic kept in temple and palace libraries. Once a dead person was declared innocent they became an akh, a 'transfigured' spirit. Magical figurines were thought to be more effective if they incorporated something from the intended victim, such as hair, nail-clippings or bodily fluids. The wands were engraved with the dangerous beings invoked by the magician to fight on behalf of the mother and child. Her books include Votive Offerings to Hathor (Griffith Institute) and Handbook of Egyptian Mythology (ABC-Clio). Private collections of spells were treasured possessions, handed down within families. It is not until the Roman period that there is much evidence of individual magicians practising harmful magic for financial reward. There were even spells to help the deceased when their past life was being assessed by the Forty-Two Judges of the Underworld. Music and dance, and gestures such as pointing and stamping, could also form part of a spell. Since demons were thought to be attracted by foul things, attempts were sometimes made to lure them out of the patient's body with dung; at other times a sweet substance such as honey was used, to repel them. Collections of healing and protective spells were sometimes inscribed on statues and stone slabs (stelae) for public use. The dead person's soul, usually shown as a bird with a human head and arms, made a dangerous journey through the underworld. This might involve abstaining from sex before the rite, and avoiding contact with people who were deemed to be polluted, such as embalmers or menstruating women. In popular stories such men were credited with the power to bring wax animals to life, or roll back the waters of a lake. Human enemies of the kings of Egypt could also be cursed during this ceremony. A spell usually consisted of two parts: the words to be spoken and a description of the actions to be taken. Amulets of Ancient Egypt by Carol Andrews (British Museum Press, 1994), 'Witchcraft, Magic and Divination in Ancient Egypt' by JF Borghouts in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East edited by JM Sasson (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1995), Magic in Ancient Egypt by Geraldine Pinch (British Museum Press/University of Texas Press, 1994). Private collections of spells were treasured possessions, handed down within families. Magical figurines were thought to be more effective if they incorporated something from the intended victim, such as hair, nail-clippings or bodily fluids. The mummified body itself was protected by amulets, hidden beneath its wrappings. In major temples, priests and priestesses performed a ceremony to curse enemies of the divine order, such as the chaos serpent Apophis - who was eternally at war with the creator sun god. Some have inscriptions describing how Horus was poisoned by his enemies, and how Isis, his mother, pleaded for her son's life, until the sun god Ra sent Thoth to cure him. A type of magical stela known as a cippus always shows the infant god Horus overcoming dangerous animals and reptiles. They are shown stabbing, strangling or biting evil forces, which are represented by snakes and foreigners. Egyptians of all classes wore protective amulets, which could take the form of powerful deities or animals, or use royal names and symbols. In Egyptian myth, magic (heka) was one of the forces used by the creator to make the world. Angry deities, jealous ghosts, and foreign demons and sorcerers were thought to cause misfortunes such as illness, accidents, poverty and infertility. This kind of magic was turned against King Ramesses III by a group of priests, courtiers and harem ladies. The most respected users of magic were the lector priests Priests were the main practitioners of magic in pharaonic Egypt, where they were seen as guardians of a secret knowledge given by the gods to humanity to 'ward off the blows of fate'. Collections of funerary spells - such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead - were included in elite burials, to provide esoteric magical knowledge. The spells were often targeted at the supernatural beings that were believed to be the ultimate cause of diseases. Detail from an ivory wand

Ideally, the magician would bathe and then dress in new or clean clothes before beginning a spell. The doctor may have proclaimed that he was Thoth, the god of magical knowledge who healed the wounded eye of the god Horus. Images of Apophis were drawn on papyrus or modelled in wax, and these images were spat on, trampled, stabbed and burned. This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. Dawn was the most propitious time to perform magic, and the magician had to be in a state of ritual purity. Horus Another technique was for the doctor to draw images of deities on the patient's skin. All Egyptians expected to need heka to preserve their bodies and souls in the afterlife, and curses threatening to send dangerous animals to hunt down tomb-robbers were sometimes inscribed on tomb walls.